The Beginning of the Taotao Håya-Unangan (Chamorro-Aleut)[1] Clan:

The Legacy of John Fratis and His Descendants

Bernard T. Punzalan

Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project™

© August 20, 2014

Background

In a previous article I summarized a little on John Fratis, a “Chamorro,” who made his way to Alaska around March 1869 as a whaler. I was so intrigued by this discovery I decided to take a journey to research more about him, his family and their descendants.

I am fortunate to have made contact with and collaborate with Byron Whitesides, an Unangan (Aleut) with kin who have married into the Fratis family and maintains a genealogy database on his relatives. I have therefore incorporated some of his data into the Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project database. Coincidently, Byron was in the military, was stationed on Guam and his son was also born there; such a small world with blessings indeed.

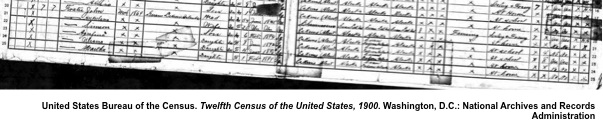

To recap the information from the 1900 Census that was the impetus for this write-up, John Fratis was listed as being married to Aklina (Akalina) Krukoff, an Unangan, born around 1872. She was also the daughter of Chief Nikolai Ivanov Krukov and Ekaterina “Katherine” Kriukov[2]. That Census also listed four of their children living with them on Saint Paul Island, Alaska: Agrafina (b. 1892), Simon John (mostly recorded as Simeon b. 1894), Julia/Ouliana (b. 1898/1896), and Martha (b. 1899). John had died in 1906.

As I continued with this journey, I discovered that John Fratis seems to have had a prior marriage with another woman also of Unangan descent. At this point I have not been able to identify her; however, they had at least three children: Susanna (b. 1875), Ellen (b. 1883) and John Jr. (b. 1886).

Fratis Surname

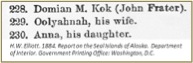

The surname Fratis seems to be tied to Portuguese descent; however, it is uncertain at this point if that was John’s real surname or phonetically spelled name among the possibilities. However, on July 1, 1870 (one year after John’s arrival at St. Paul), a list of resident natives of St. Paul Island was recorded by Philip Volkov and later republished in a variety of U.S. Government and Congressional documents. Although the name John Fratis does not appear, quite close to the end of the list appear the names “Domian M. Kok (John Frater), Oolyahnah, his wife, Anna, his daughter.” I have flagged these names as a potential of being the beginning of John’s first family in St. Paul.

St. Paul Island, Alaska a.k.a Fur-Seal Islands

The history of St. Paul is quite an interesting one. St. Paul is the largest of the Pribilof Islands of Alaska and was initially uninhabited until Russian fur traders gathered and brought Aleuts (some historians argue they were forced/enslaved) in the 18th century to the Pribilof Islands to hunt seal for them, and eventually colonized the Islands.

John Fratis and his family were nearly at the beginning of history under the U.S. when it purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867. Even while under the jurisdiction of the U.S. the Unangans experienced their share of more injustices that would eventually, albeit many years later lead to a government settlement for their people in 1979.

In one 1873 recording by a Treasury Agent for the Seal Islands, he refers to John Fratis as "a Spanish creole, a native of the Ladrones Islands." Because John was an employee of the Alaska Commercial Company (exclusive licensee of the Pribilof Islands), it seems that there was some kind of attempt by the company to convince the Unangan chiefs to adopt John as a native in order that he may share in the privilege of labor and pay as with the rest of the natives. However, this was contrary to prior customs and a practice influenced by previous Russian law and principles and at the time was not permitted.

However, the historical documents would reveal that this custom and practice would change at a later date and John would be granted the privilege and pay but under a different class of native category. I would suspect that his marriage to an Unangan woman and their children (as well as other outsiders that married into the Unanagan clans) may have influenced this change.

There is quite a bit of other literature, testimony and reports that discuss the injustices and abuse of the Unangan people over fur seals. Because of all the literature available on this topic it was not too difficult to find some information on John, his family and descendants, while other information remains research-in-progress.

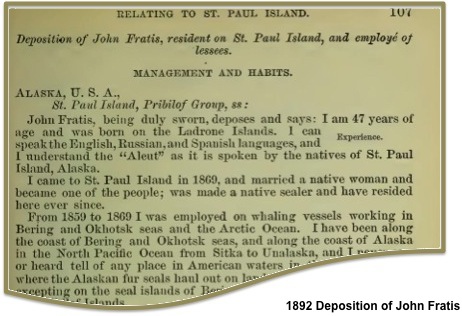

During what is known as the Fur-Seal Arbitration among many documents and reports, the documents included a deposition statement from John Fratis from 1892. John was an employee of the Alaska Commercial Company; a company that was awarded a lease to the Pribilof Islands for the purpose of sealing. Below is an extract of his deposition that gives some of his background, knowledge and his role in sealing:

John Fratis, being duly sworn, deposes and says: I am 47 years of age and was born on the Ladrone Islands. I can speak the English, Russian, and Spanish languages, and I understand the "Aleut" as it is spoken by the natives of St. Paul Island, Alaska.

I came to St. Paul Island in 1869, and married a native woman and became one of the people; was made a native sealer and have resided here ever since.

From 1859 to 1869 I was employed on whaling vessels working in Bering and Okhotsk seas and the Arctic Ocean. I have been along the coast of Bering and Okhotsk seas, and along the coast of Alaska in the North Pacific Ocean from Sitka to Unalaska, and I never saw or heard tell of any place in American waters in that whole region, where the Alaskan fur seals haul out on land or breed, excepting on the seal islands of Bering Sea known as only on Pribilof Islands.

From the time I settled here in 1869 until 1882 or 1883, there was no trouble at all in taking 85,000 seals on St. Paul Island between June 1 and July 30, and we often got that number by July 20.

In those days we used to get plenty of seals on the Zoltoi sands near the Reef rookery, and now there are none there. I have worked on the sealing grounds at everything there is to do, from driving to clubbing, and preparing the skins for shipment. When Mr. Webster had charge of the killing at Northeast Point, where he used to kill from 25,000 to 35,000 seals in a season, I generally did the cooking there, and I cooked seal meat every day, and we all ate it, and our people live on seal meat, yet I never saw a sick or a diseased seal or a carcass that was unfit for food.

I have driven seals from all the rookeries and under the directions of several chiefs, and I know the orders were always very strict about the care we must take of the seals on the road. No drives were made in warm weather; the seals were not hurried, but every once in a while they were allowed to stop and rest. The men who did the driving were relieved from time to time, so that no man should get too cold on the drive, and when the sun came out warm the drive was always abandoned and the seals allowed to go into the sea. I never saw the seals overdriven or overheated, nor have I ever seen a seal die on the drive except one or two occasionally smothered.

The drivers carry their knives along, and when a seal dies they skin him and the skin is brought to the salt house and counted in with the others. An overheated seal would not be worth skinning, and for that reason the company agent is particular that the seals are not overheated. I have clubbed seals, too, and at present I am a regular clubber.

We know a cow seal on sight, and when we find one on the killing grounds we take care she is not injured. Very few cows get into the drives before the middle of August, and then we are only driving and killing a few hundred a week for food.

All cows killed on the seal islands are killed accidentally, and it occurs so seldom that I do not think there has been to exceed 100 since I came to the island in 1869. So carefully has this been guarded that when we used to be allowed to kill pup seals in November we had to examine and separate the sexes and kill none but males.

The seals came to the islands in spring and they came from the southward. The first bulls arrive late in April or very early in May, and they are coming along till June. The bachelors come in May, the older ones first, and thev continue coming till July, when the younger ones arrive. The cows appear about the 10th of June, and they are all on the rookeries about the middle of July.

The pups are born soon after the arrival of the cows, and they are helpless and cannot swim, and they would drown if put into water. The pups have no sustenance except what the cows furnish and no cow suckles any pup but her own. The pups would suck any cow if the cow would let them.

After the pup is a few days old the cow goes into the sea to feed and at first she will only stay away for a few hours, but as the pup grows stronger she will stay away more and more until she will sometimes be away for a week.

I do not think the bachelors go to feed from the time they haul out until they leave the islands in November, for I have observed the males killed in May are fat and their stomachs full of fish, mostly codfish, while the males killed in July and afterwards are poorer and poorer and their stomachs are empty. I know the bulls do not eat during their four months stay on the islands.

In August the families, or harems, break up and the cows scatter all over the rookeries, and the bulls begin to go away late in August and all through September, so that very few are left in October. The cows and bachelors begin to leave in October and November, but their going is regulated somewhat by the weather.

Cold stormy weather, with sudden heavy frost, will drive them off sooner, so that the islands will be deserted by December 15, while warm weather will keep plenty of bachelors here until late in January, when I have known them to be driven and killed for food. When the seals leave the island they go southward and through the passes of the Aleutian Islands into the Pacific Ocean.

It was in 1884 that I first noticed a decrease in the seals, and it has been a steady and a very rapid decrease ever since 1886, so that at present there is not one quarter as many seals on the island as there was every year from 1869 to 1883.

I have known of one or two schooners operating in Bering Sea as early as 1877 or 1878, and they were on the rookeries occasionally during the past ten years; but they cannot damage the seal herd much by raiding the rookeries, because they cannot take many, even were they permitted to land, which they are not by any means.

The schooners increased every year from the time I first noticed them until in 1884 there was a fleet of 20 or 30, and then I began to see more and more dead pups on the rookeries, until in 1891 the fleet of sealing schooners numbered more than a hundred and the rookeries were covered with dead pups.

It is my opinion that the cows are killed by the hunters when they go out in the sea to feed, and the pups are left to die and do die on the island.

I never knew of a time when there were not plenty of bulls for all the cows, and I never saw a cow seal—except a two-year old—without a pup by her side in the proper season.

I never heard tell of an impotent bull seal, nor do I believe there is such a thing, excepting the very old and feeble, or badly wounded ones. I have seen hundreds of idle vigorous bulls upon the rookeries, and there were no cows for them. I saw many such bulls last year. The pups do not learn to swim until they are 6 to 8 weeks old, and after learning they seem to prefer to be on the land; and I think they would not leave the islands only for the cold weather, or it may be they follow the cows to sea after being weaned.

If the seal were let alone in the water we could manage them so as to again build up the rookeries. We are so familiar with their habits and they are so accustomed to us that there is no difficulty in managing them so as to make them increase. They are easy to handle, the little pups are not shy of us, and even when they are older in the fall they can be handled much easier than sheep. I can manage seals better than I can some of the sheep brought on the islands and which I have been sent to catch.

John Fratis.

Subscribed and sworn to before me, an officer empowered to administer oaths under section 1976, Revised Statutes of the United States, this 10th of June, 1892, at St. Paul Island, Alaska.

Wm. H. Williams,

Treasury Agent in charge of Seal Islands.

Fratis Diaspora

With regards to John’s children from his first marriage, and as of this writing, most, if not all, of the Fratis family that carry the Fratis surname and continue to reside in St. Paul appear to be the descendants of John Fratis, Jr. His daughter Susanna died at the age of 17 in 1892, and I was not successful on finding any additional information on his daughter Ellen.

With regards to John’s second marriage to Aklina (Akalina) and their children, some seemed to have relocated to parts of Oregon State. Part of the reason for this stems from education opportunities offered by the Salem Indian Training School at Chemawa, Oregon.

The Salem Indian Training School was maintained by the Government at Chemawa, Oregon and allowed the young people from the Pribilofs to receive training in addition to what they may have obtain at the local schools maintained by the Bureau of Fisheries on St. Paul. In 1915, Agrifina, Julia (Ouliana) and Martha Fratis left aboard the Bureau of Fisheries’ supply ship to San Francisco, enroute to the school and began their attendance in October 1915.

Agrifina Martha Fratis left the Salem Indian Training School on June 15, 1919 but never returned back to St. Paul. In 1920, they were at Marshfield, Oregon.

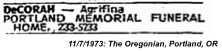

Sometime in 1929, Agrifina married Grant Emerson DeCorah[3]. In the 1930 Census Agrifina and her husband were recorded as living in Chemawa, Oregon and then in the 1940 Census living in Everett, Washington. A couple of years later, Grant died[4] in Tacoma, Washington, 1942. Sometime after Grant’s death, Agrifina relocated back to Portland, Oregon. She died in Portland, Oregon, 1973.[5]

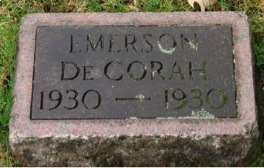

Based on information obtained from the Salem Pioneer Cemetery[6], Agrifina and Grant had an infant son named Emerson DeCorah who unfortunately lived only for a few days. Although there is conflicting information as to whom Emerson’s parents may be, the Cemetery database lists Agrifina and Grant on the death certificate as his parents. It does not appear that they had any other children.

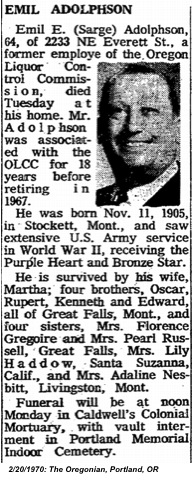

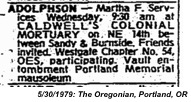

In the 1940 Census, Martha was residing with her sister Julia in Portland. Sometime in the 1940’s Martha married Emil Ebenhart Adolphson and died in 1979 at Portland, Oregon[7]. Emil died[8] on 1970 in Portland, OR. Martha and Emil were active members of the U.G. McAlexander Chapter 72, Military Order of the Purple Heart and Oregon Military Order of the Purple Heart. It does not appear that they had any children.

In 1920, Julia (also known as Ouliana) completed a course of study at the Salem Indian Training School and was subsequently given the responsibilities of acting as a matron in one of the building for smaller girls.[9] The Bureau found it doubtful that she and her mother would ever return to St. Paul. As of December 31, 1921, Mrs. Aklina Fratis and her daughter Julia were still at the Salem Indian Training School and apparently employed there.[10]

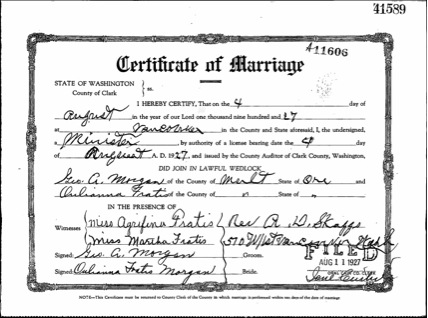

In 1927, Ouliana married Geo A. Morgan. By the 1940 Census, Julia was listed as divorced and living with her sister Martha in Portland, Oregon. Through various articles in The Oregonian newspaper “Julia Fratis Morgan” seemed to have been active with assisting the Chemawa Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and at one time served as the Vice President of the Blue Triangle club of the Chemawa YWCA.

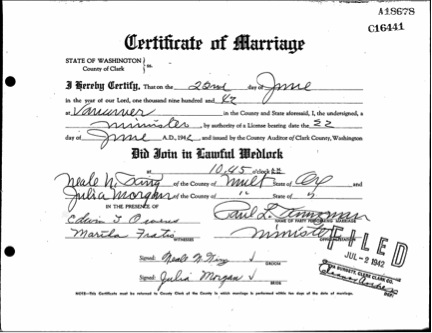

Julia later entered into her second marriage with Neale Noe King[11] in 1942. By 1977 Julia had passed away in Portland, Oregon[12]. It does not appear that Julia had any children from either of her two marriages.

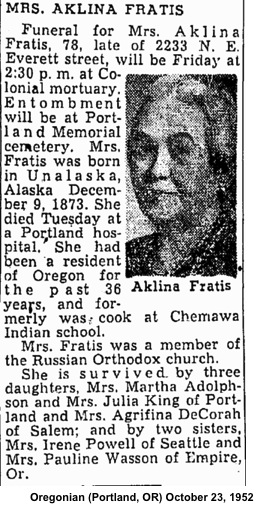

I was fortunate to find a copy of Aklina’s obituary. She died at Portland, Oregon in 1952[13].

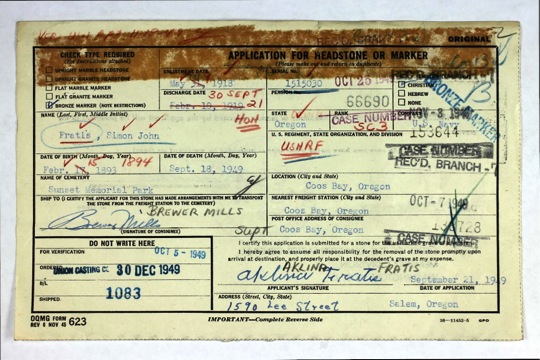

Sometime before 1920, John’s son Simon, relocated to Marshfield, Oregon. Simon served a few years in the U.S. Navy Reserves during World War I. It does not appear that he was ever married or had any children. He died in 1949 and is buried at the Sunset Memorial Park, Coos Bay, Oregon[14]. Apparently his birth date on the cemetery marker was never corrected as depicted in the cemetery marker application completed by his mother Aklina.

World War II Impact: Evacuation and Internment

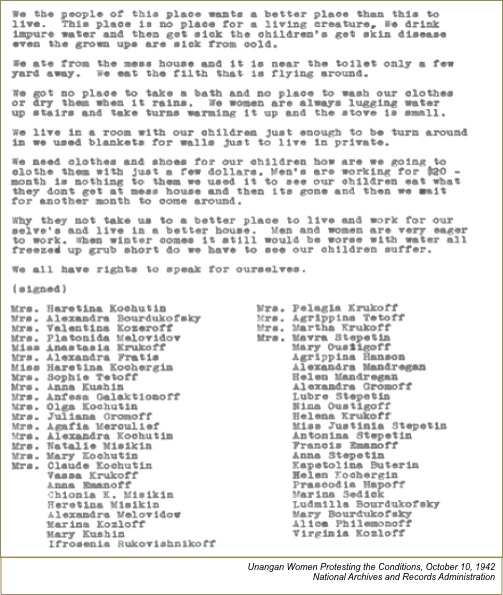

The Chamorro people of the Mariana Islands were not the only natives affected by war and imperialism. The Pribilof Islands and its inhabitants were also affected. They were affected to the point that the U.S. evacuated the residents of the Pribilof Islands in 1942. The Unangan people from St. Paul were relocated and interned at an old abandoned cannery facility in Funter Bay, Alaska.

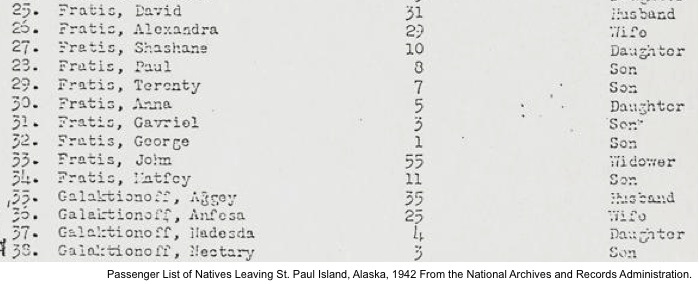

The image below lists some of John Fratis Sr.’s descendants who were evacuated and interned at the abandoned Funter Cannery, Funter Bay, Alaska. It does not appear that any of his descendants died while interned.

The internment conditions were very deplorable and several people died while interned under the jurisdiction of the U.S. While several literature and websites indicates that 32 people died while interned at Funter, I counted 40 (18 from St. George Island and 22 From St. Paul Island) from a list that was compiled by the Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association Inc. and presented to Congress.

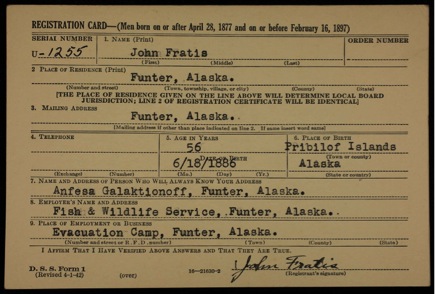

Considering internment conditions, the draft registration card of John Fratis Jr. appears to be like adding salt to the open cut wound. His address on the draft registration card reflects the internment address of Funter, Alaska.

Unfortunately, it was not until Congress passed the Aleut and Pribolof Islands Restitution Act of 1988 where the Unangan people received a reparation settlement as a result of their internment during World War II.

John Fratis Jr. and his family

As I mentioned earlier it appears that the Fratis surname survives from John Jr.’s descendants. John Jr. was married to Snandulia Kozeroff (b. 1890); the daughter of Stepan Kozeroff and Anastasia Nozekoff[15]. They had nine children[16]:

1.Gabriel Fratis[17] (b. 1906)

2.Christopher Fratis[18] (b. 1908)

3.David Fratis (b. 1911)

married Alexandra Buterin (b. 1913)

4.Anfesa Fratis (b. 1917)

married Aggey Glaktionoff (b. 1906)

5.Anna Fratis (b. 1919)

6.Martha Fratis (b. 1923)

married William Shane, Sr. (b. 1917)

7.Olga Ada Fratis (b. 1925)

8.Taheesi Fratis (b. 1926)

9.Matfey Fratis, Sr. (b. 1931)

m. Maria Emanoff (b. 1935)

Research-in-progress

Currently, I have not been able to bridge John Sr.’s heritage with his Chamorro ancestry. The primary reason is not an uncommon one for this time period. There continues to be a historical gap on obtaining detail Census documents during the Spanish occupation from 1759 through 1896 (gap years between available census documents 1758 and 1897).

In the future, I hope to have more information and stories to share on the Fratis family.

Bibliography

Bureau of the Census. 1900. Twelfth Census of the United States. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration

Bureau of the Census. 1910. Thirteenth Census of the United States. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration

Bureau of the Census. 1920. Thirteenth Census of the United States. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration

Bureau of the Census. 1930. Fourteenth Census of the United States. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration

Bureau of the Census. 1940. Fifthteenth Census of the United States. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration

Bureau of Fisheries. 1921. Alaska Fishery and Fur-Seal Industries in 1920. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC.

Bureau of Fisheries. 1922. Alaska Fishery and Fur-Seal Industries in 1921. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. 1982. Personal Justice Denied. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Find a Grave. Accessed on August 12, 2014 from: http://www.findagrave.com

National Archives and Records Administration. Applications for Headstones for U.S. Military Veterans, 1925-1941. Washington, D.C.

National Archives and Records Administration. Passenger List of Natives Leaving St. Paul Island, Alaska, 1942 - 1942. Washington, D.C.

Oregonian, The. Portland, Oregon.

State of Oregon. Oregon Death Index, 1903-1998. Oregon State Archives and Records Center: Salem, Oregon.

Treasury Department. 1898. Seal and Salmon Fisheries and General Resources of Alaska, Volume 1. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC

Washington State Archives. Olympia, Washington: Washington State Archives.

Whitesides, Byron J. Personal communications and accessed on August 12, 2014 from: http://www.geni.com/people/John-Fratis/6000000022542954408

[9] Bureau of Fisheries. 1921. Alaska Fishery and Fur-Seal Industries in 1921. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC.

[10] Bureau of Fisheries. 1922. Alaska Fishery and Fur-Seal Industries in 1921. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC.