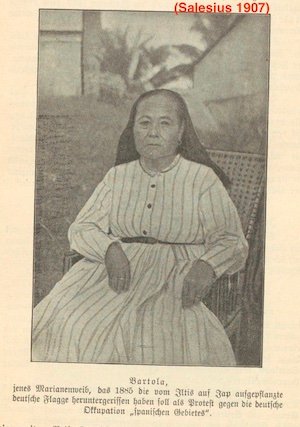

There are several good write-ups on Bartola Taisague Garrido, but as I was looking into the Garrido family trees more, I stumbled across additional information on her. Some of this information may already have been previously written about and accessible via the internet, while other components were derived from additional literature.

Thanks to Pale’ Eric, in an 1872 manifest document embarking out of Honolulu to Guam she was recorded at the age of 25. This means she was born around 1847 on Guam. It is currently unknown why she was in Hawaii.

In 1875, Bartola was a passenger aboard the controversial schooner Arabia, owned by “Bully” Hayes, a known pirate and blackbirder. The Arabia fled Guam with some “deportado” passengers also onboard. It came into trouble and adrift in the waters of Palau. In the area and to the rescue happened to be Crayton P. Holcomb, an American, and Captain of the schooner Scotland. From that incident, a marriage between the two resulted. In addition, Holcomb ended up taking possession of the Arabia and renamed it the Doña Bartola, in honor of his wife.

Bartola is well known in Micronesia history to have defied the German government and refused to recognize its sovereignty claim over Yap in 1885. She was a staunch advocate of the Spanish government and Catholic practices. All indication from historical documents demonstrates that she was smart, courageous, and diplomatic enough to finesse and navigate her way through a culture of foreign masculinity as well as secure the trust and support of the native Chiefs and people of Yap. She was also a woman of linguistic talent and knew how to speak CHamoru, Yapese, Spanish, English and German.

I still have not been able to connect her Garrido lineage with others. But, since the 1700s, there have been several Garrido men who served as Spanish soldiers. Some held key positions. For example, in relation to this era, in 1884, there was an Infantry Second Lieutenant Miguel Garrido, who also served as The Government Secretary. Although Father Aniceto Ibanez had her name initially listed as Bartola Taisague, in future documents her name is recorded as Bartola Garrido y Taisague. Also, Påle’ Eric indicated she may have been also known as Bartola Taisague y Delgado, hinting that Taisague was her mother’s surname and Delgado her mother’s middle name. Having a Garrido surname at the time may have had its perks and influences. There is no mention of her role, if any, in the 1875 “deportados,” incident.

We also know that she and two of her nephews, Ramon/Raimundo and Juan, were described as the only Catholics in Yap in 1887. Ramon was already of adult age to marry, and Juan was about 11 years old in 1887. However, their last names were not recorded.

Some additional interesting accounts of Bartola’s Holcomb-in-laws are recorded. It appears that her husband never told his family about his wife. This is evidenced in a volley of letters between him and his family. Holcomb also seemed to be the financial caretaker of this family in Connecticut. His sister Arlesta, was the most active and persistent in seeking more information about her deceased brother and possessions he may have left behind for his family. In June 1886, the family received a letter from the State Department officially informing them that Holcomb was killed in May 1885. A few months later, the family received its second whammy: a letter dated 16 August 1886, from Bartola. The letter was addressed to her mother-in-law in response to a letter she last sent to her son.

Not only the family could not believe that Holcomb died in St. Matthias Island, Papua New Guinea, but were further shocked to learn of Holcomb’s wife Bartola and more so the opening salutation of the letter, which read, “Dear Mother.” There is no indication if the Holcomb family ever responded to Bartola’s letter or accepted her marriage with Crayton Holcomb.

However, these two shocking pieces of information did not stop Arlesta from continuing to write and press the consulates at several locations. The consulate office in Hong Kong finally responded with information that included some from Captain David O’Keefe in Yap. O’Keefe reiterated to the family Holcomb’s poor financial situation and his reputed wife Bartola.

In Arlesta’s family’s quest over the years to find more information on Crayton Holcomb, her grandson Louis received some information from the Catholic Mission in 1970. He was informed that Fernando Ruepong, an older native Yapese, conveyed some of his recollection regarding Bartola and her husband Crayton. To the natives of Yap, Bartola was known as “Maram.” Maram is not a native word, but is believed to be a corruption of “Madam.” In some Levesque sources, she is sometimes addressed as Madam Bartola. Ruepong also mentions a Juan Borja, and was believed to be Bartola’s brother. Ruepong further stated that Bartola was even known as “Maram Holcomb,” or “Maram Borja.” Ruepong confirmed that Bartola is buried in a cemetery on Yap; however, the Catholic missionaries confirmed that her grave is unmarked. Additionally, they admitted that they found it strange that they did not have any death records on Bartola or any baptismal recordings. Indeed, that is strange, because in a narrative of Father Joaquin Llevaneras visit to Yap from 1 December 1886 to 28 August 1887, he reported that Bartola and Governor were the Godparents of a child baptized with the name Leon, one of the first Carolinian children to receive baptism on 2 February 1887. Llevaneras also reported that since then, about thirty islanders were also baptized.

Sometime after her first husband Holcomb died in 1885, and likely during the German’s possession of Yap beginning in 1899, she remarried a German gentleman with the surname Beck. Other than a couple of reports that listed Bartola as Bartola Beck, I could not find any information about her German husband. The first occurrence of her being listed as Bartola Beck is a 19 May 1900 report from the German Imperial District Administrator of Yap.

In Pascual Artero’s autobiography, he indicated that his later-to-be wife, Asuncion Cruz, and four of her sisters were sent to Yap as teachers. While there, they lived with Bartola and that is where he first met Asuncion. Because of the war between the U.S. and Spain, the Cruz sisters would later board a Japanese schooner to try and get back to Guam. However, the schooner ended up going to Palau and then onto the Bonin Islands. It’s also interesting to note that when the Cruz sisters were in the Bonin Islands, Artero said that they lived with a lady of Guam, who was married to an Englishman. Levesque thinks that the Englishman that Artero was referring to might have been Richard or his son Henry Millenchamp. However, from my records, there was only one well-known woman from Guam in the Bonin Islands in the 1800s, and she was Maria Castro delos Santos. She was the CHamoru matriarch of the Bonin Island descendants, whose husband was Nathaniel Savory, an American. But the timelines for this lady to be Maria seem a little sketchy though because she purportedly had died sometime in 1890 and the Cruz sisters were likely in the Bonin islands mid-to-late 1898 or early 1899. I mention this here as a bookmark in hopes of later resolving: Who was the lady from Guam in the Bonin Islands that Artero mentions? Was Maria Castro delos Santos still alive in the late 1890s?

On 23 October 1884, Bartola’s husband, Holcomb, presented a petition that was translated into Spanish by Bartola. He, Bartola, and eight other people signed the petition. It was addressed to the Governor of the Philippines requesting that a governor be assigned to Yap and Spanish rule be established in Yap and Palau. The petition gave indication that Bartola had a strong religious background and was very loyalty to Spain. Unfortunately, when the Governor acknowledged the petition, he addressed only the men and not Bartola. But even so, the Spanish government did not act fast enough. By August 1885, Germany had exercised its sovereignty and claimed possession of Yap. But that didn’t stop Bartola from flying Spain’s flag on a tree.

In 1886, the Spanish dispatch boat, Marques del Duero, arrived in Yap. On 28 April 1886, the Commander met with Bartola and provided her with her appointment as the Interpreter in Yap. Moments later, Mr. Robert Friedlander, a German, who lived next door, came into Bartola’s house and informed them that he just received a letter from the German Counsel in Manila, that his government now recognizes Spain’s sovereignty over Yap.

The following day, on 29 April 1886 at 9:00am, an assembly with Yap’s native Chiefs took place on a plain of Tapelau with the Commander of the Spanish dispatch boat Marques del Duero. The ceremonies commenced with the official raising of the Spanish flag and possession over Yap, and the Commander delivered the Deed of Possession proclamation over Yap.

A few months later, the Spanish frigate Manila arrived in Yap on 29 June 1886. Its passengers included the first governor of the Carolines, Manuel de Eliza, along with a small contingent of Spanish officials, several Filipino soldiers and convicts to help build the governor’s residence and military barracks on one of the small islands in Yap’s main bay; and six Capuchin missionaries. When they arrived, Bartola Garrido was one of the first people to greet the missionaries at the dock.

The Spanish government had difficulty purchasing land in Yap from the natives to set up its administration and other facilities. And because of that, Bartola offered some land behind her property for 400 pesos. The property was determined to be a strategic point of interest and there was room for the installation of a Government House, barracks, infirmary, officers' house, chapel. Therefore, a Bill of Sale and Deed were drawn up and executed for the Spanish government’s purchase of the island named Apelelan (aka Herrans) from Bartola.

Although, Bartola was officially under the Spanish government’s services as the Interpretor and school teacher in Yap she had a hard time receiving payment from the government. In fact, a letter dated 29 August 1887 from Mariano Torres, the Political Governor of Caroline Islands and Palau, was addressed to the Governor General of the Philippines, requesting support to pay Bartola. The Spanish Government archives contained a pathetic note from Bartola to the Government Secretary in Yap, Mr. Gil, asking for help one night because she did not even have oil for her lamp. Bartola had also been renting part of her house to a man who had not paid his rent for months. So it seems that some people took advantage of Bartola’s kind and generous heart for granted.

A destructive typhoon hit Yap in January 1895. On Bartola’s property the typhoon took out many of the lodgings that were built. Her house was the only one left, but was also badly damaged.

A few more years passed with some key events that would transform colonial powers in the Pacific. After Spain lost the war against the U.S., Germany purchased Yap and many other islands in Micronesia from Spain. On 3 November 1899, the German government officially took over Yap with a handover ceremony. Bartola was said to have been “crying her heart out,” during the ceremony.

The German administration did lease some of Bartola's land. After Bartola’s passing away, the German government took over ownership of all her land. Contrarily, some say that Bartola was still alive when the Japanese took over the administration of Yap from the Germans.

Bibliography

____. 1947. Education & Social Service; Native Culture (Index Cards). United States Navy. Retrieved from: https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu

Artero, Pascual. 1984. Las golondrinas no volveraan, de Mojacar a Guam: Autobiografia del mojaquero Pascual Artero "el rey de Guam" (Spanish Edition).

Costenoble, Hermann H. L. W. 1905. "Die Marianen." Globus Magazine 88, no. 1, pp. 49; no. 3, pp. 7281; no. 4, pp. 9294

Cruz, Karen A. 2005. Hinanao: Travelers and Descendants of Travelers (p23). Self-published, Hagåtña.

Forbes, Eric. 2011. Bartola Garrido. Retrieved from: https://paleric.blogspot.com/2011/06/bartola-garrido.html

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. 1975. “A Yankee Trader in Yap: Crayton Philo Holcomb.” Retrieved from Micronesian Seminar: https://micronesianseminar.org/article/a-yankee-trader-in-yap-crayton-philo-holcomb/

Hezel, Francis X., SJ, and M.L. Berg, eds. 1980. Micronesia: Winds of Change. A Book of Readings on Micronesian History (p353-354, p365-366). Saipan: Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. 1983. The First Taint of Civilization: A History of the Caroline and Marshall Islands in Pre-Colonial Days, 1521-1885. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1983.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. 1995. Strangers in Their Own Land: Century of Colonial Rule in the Caroline and Marshall Islands. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1995.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. 2003. Strangers in Their Own Land: A Century of Colonial Rule in the Caronline and Marshall Islands (p10-11). University of Hawaii Press. Honolulu, HI.

Ibañez del Carmen, Aniceto, OAR, and Francisco Resano del Corazón de Jesús, OAR. 1998. Chronicle of the Mariana Islands: Recorded in the Agaña Parish Church 1846-1899 (p66-67). Translated, annotated, and edited by Marjorie G. Driver and Omaira Brunal-Perry. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam.

Laun, Carol. 1998. The Adventurous Life and Mysterious Death of Captain Crayton Holcomb. My Country, Volume 32 No. 2. My Country Society, Inc. Litchfield, CT. Retrieved from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5802c4d9414fb5e45ce4dc44/t/59998ddca5790aaa7eab42cc/1503235556802/Holcomb%2C+Crayton%2C+Capt..pdf

Levesque, Levesque. 2004. History of Micronesia, Volume 29. Levesque Publications. Quebec Canada

Levesque, Levesque. 2004. History of Micronesia, Volume 31. Levesque Publications. Quebec Canada

Levesque, Levesque. 2004. History of Micronesia, Volume 33. Levesque Publications. Quebec Canada

Levesque, Levesque. 2004. History of Micronesia, Volume 37. Levesque Publications. Quebec Canada

Levesque, Levesque. 2004. History of Micronesia, Volume 38. Levesque Publications. Quebec Canada

Madrid, Carlos. 2006. Beyond Distances: Governance, Politics and Deportation in the Mariana Islands from 1870 to 1877 (p145). Saipan: Northern Mariana Islands Council for Humanities.

Montaner and Simon (edittores). 1900. La Ilustracion Artistica, TOMO XIX. Monatner Y. Barcelona, Spain. Retrieved from: https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QacsiiFd4ZoiDZiOTXgEnNzouNbvJZS4BuCHVLgyu3AgQTh15QXfuX5h776HBXEPYSSHV3jNV7TYQyWQQ0hu-cmGjRmEI4RVUeciG_unydcvYzanX9Sk5ePO3J6_XqMdno8l90Qoz-iWPGCeD-MPFNyOrAtc4YZTbMtS0as5kIM42g7t3EPeZEC5a0KA5p96TFTDQpo4DuIgmaPyA00mnGkZv1Vg5qI3Shm610Rlo8_70ZXj5gpHMM8tahdIk1FD7Zatu_WtlXpz8sK7YL0btKjlPpkokw

Salesius, Pater. 1903. Die Karolinen-Insel Jap.: ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis von Land und Leuten in unseren deutschen Südsee-Kolonien (p15). Berlin: W. Süsserott. Retrieved from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b58752&view=1up&seq=7

Tolentino, Dominica. 2019. Famalao’an Guahan: Women in Guam History (p20-21). Guampedia. Mangilao, Guam.